Federico Zuccaro

Self Portrait

‘Galleria degli Uffizi’

From commons.wikimedia.org

Federico ZUCCARO

From fineart-china.com

Federico Zuccaro ranks among the major painters of the late 1500s. He was a proponent of the Mannerist style, which formed a bridge between the Renaissance and Baroque periods. He trained in his older brother’s studio, assisting Taddeo on important commissions. Between 1563 and 1565, Federico was in Venice and Florence, returning to Rome in 1566, the year of his brother’s death. He worked on the cupola frescoes of the Duomo in Florence, and became court painter to Philip II of Spain.

(getty.edu)

Renaissance Rome

From iicbelgrado.esteri.it

Renaissance Rome

From iicbelgrado.esteri.it

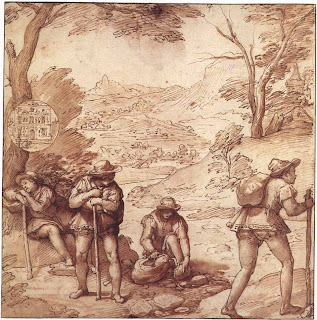

‘Figures debout et agenouillées’

Current Loc Musée des Beaux-Arts

From commons.wikimedia.org

In 1565, after Taddeo‟s death, Federico obtained a commission to work in Florence as a decorative painter for the wedding of the Grand Duke de‟Medici and Joanna of Austria. He would remain in the city for nearly a year, working on this and other commissions. In late 1566 he returned to Rome and remained there on and off until the spring of 1574, when he then traveled to Antwerp and, from there, on to London. Zuccaro‟s central purpose in traveling to London was so as to paint (now lost) portraits of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and the Queen. What is certain is that Zuccaro obtained a letter of introduction from the Tuscan Ambassador Chiappino Vitelli, who was then in Antwerp. The letter, directed to the Earl of Leicester, recommends Zuccaro as a respected master painter (and fellow countryman of Vitelli‟s) upon whom both Leicester and the Queen could rely. Although very few of Zuccaro‟s English works remain, there are some extant studies (as drawings) for portraits of Leicester and the Queen, suggesting that Vitelli‟s intercession provided Zuccaro with some support in his (apparent) desired entrée into the English court.

(hanseworth.com)

Federico spent over a year in London, living in the house of the Earl of Leicester, waiting to see if Queen Elizabeth would assign him a major painting commission (she didn't) and painting her portrait and that of the Earl, among others—and the Doge and Senate of Venice. Mundy suggests that "while Taddeo might be said to revel in the local artistic dialogue, Federico would aspire, in his drawing, painting, and his theoretical works, to a visual form of Esperanto . . . equally at home in Rome, Venice, or Madrid". Unlike Taddeo, for whom, as for Michelangelo, the human body was the primary means of conveying meaning in art, Federico used the common language of symbols (undergoing codification in the manuals of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries so that gentleman could understand the vocabulary of the new generations of artists). "When this language was decoded, it carried a specific meaning that spoke to a sophisticated, educated audience”. (spaightwoodgalleries.com)

Scenes from the Early Life of Taddeo Zuccaro

Pen and brown ink

Brown washes over black chalk

Touches of red chalk

All images from donmacdonald.com

In this series of drawings,above, Federico Zuccaro illustrated the early life of his older brother Taddeo Zuccaro, from the hardships of his early training in Rome until his first artistic triumph at the age of eighteen. In addition to the sixteen scenes from Taddeo’s life, the series includes four drawings of allegorical Virtues flanking the Zuccaro emblem. The drawings vividly convey a sense of the artist’s material and intellectual life in Renaissance Rome. Details of studio practice join depictions of precise locations, monuments, and antiquities and references to the great artistic personalities of the Renaissance, including Michelangelo and Raphael. Scholars believe that the shape of the drawings shows that they were studies for decorative ceiling panels. Because so many of the sheets contain images of Rome, they may have been intended for frescoes in the Palazzo Zuccari in Rome. In Federico’s will of 1603, he left his palazzo to the Accademia di San Luca so that it could be used as a hostel for poor, young artists coming to study in the capital. The imagery of Taddeo’s early struggles would have been an appropriate reminder for the students at the beginning of their careers.

(According to the Getty Museum website at donmacdonald.com)

Like a movie storyboard, the remaining chalk and ink drawings sequentially outline the next four years of Taddeo's life. Aside from three occasions when paired allegorical figures (Fortitude and Patience; Wisdom and Diligence; and Study and Intelligence) interrupt, the narrative proceeds with swift economy. In a few of the often oddly shaped pictures (whose outline resembles a plump pair of weightlifter's dumbbells), several moments are compressed into single scenes. In one, Taddeo appears four times: as his apprenticeship to his cousin, the painter Francesco Sant'Agnolo is rebuffed; as he wanders the streets in tears; as he is stopped in his tracks by the Palazzo Calcagni's elaborately decorated facade; and as he sketches Polidoro da Caravaggio's work, overcoming his sadness through art. Difficulty makes up a large part of the boy's first years in Rome. Just after he beholds a spectacular panorama of the Italian capital, a frightful trio confronts him on his entry to the city. Identified by inscriptions on their clothing, Servitude, Hardship and Toil drive home the point that the immediate future does not bode well for the aspiring artist. This notion is repeatedly illustrated in his labors for the minor painter Giovanni Piero Condopulos, who treated Taddeo cruelly, forcing him to toil long into the night, denying him food and preventing him from pursuing his art. In another "time-lapse" image, he makes a bed, carries water and firewood, lights the stove and cooks dinner. Throughout these hardships of Dickensian proportion, his drive to make art is undiminished. Whenever he can steal a moment from his heartless masters, he can be seen, pencil in hand, drawing determinedly on any available scrap of paper--even on the shutters of his bedroom window. Upon quitting his day job, he explores the city, sketching ancient sculptures and friezes and modern facades and frescoes, including Raphael's works at the Villa Farnesian. But life on the street is tough, and Taddeo returns to his parents' home, sick, malnourished and plagued by hallucinations. (articles.latimes.com)

Scene from Taddeo’s life

From donmacdonald.com

In no time at all, he's back on his feet. Crossing paths with the Three Graces, he again enters Rome, where he copies more masterpieces, including Michelangelo's "Last Judgment," from the Sistine Chapel. His story ends in triumph, with Taddeo raised high on a scaffold, painting the facade of the Palazzo Mattei as Michelangelo, Giorgio Vasari and others looking on admiringly.

(articles.latimes.com)

Scene from Taddeo’s life

From donmacdonald.com

This work shows the 14-year-old Taddeo gazing longingly over his shoulder at his distraught parents, as a pair of muscular angels lead him away from the small town of Sant'Angelo in Vado, where he was born, and toward Rome, where he dreamed of studying painting and drawing. Looking clueless and terrified, the 4-year-old Federico peeks out from behind his mother's dress.

(articles.latimes.com)

Scene from Taddeo's life

From donmacdonald.com

Federico Zuccaro noted that, "When (his brother Taddeo) was living in the house of Calabrese he could never make drawings in the daytime and hardly ever in the evenings, and at night he had to go to bed in the dark because he was grudged even a drop of oil for a lamp; but his desire was so great that he would get up and draw by moonlight on the windows." Here Taddeo Zuccaro has leapt out of bed half-dressed in order to frantically sketch the Tiber river, Castel Sant'Angelo, and the dome of Saint Peter's basilica under construction by moonlight. He has only had time to put on one slipper, while the rest of his clothing lies haphazardly beside the bed in the corner. Federico added many small details of everyday life: the chamber pot under the bed, the jagged board Taddeo used to support his paper, and the shutters on whose makeshift surfaces he has drawn figures. These all create a vivid impression of a young artist's material life in Renaissance Rome.

(getty.edu)

Taddeo in the Belvedere Court in the Vatican

Scene from Taddeo’s life

From donmacdonald.com

Drawing the Laocoön is of particular significance to Baroque art because it emphasizes the importance to artists of drawing from nature and from classical antiquity. It was thought that the classical masters of antiquity had a full grasp on nature, and so copying a work such as the Laocoön from the first century BC was a step in the right direction for a young learning artist. Federico drew Taddeo seated in the Belevedere Courtyard, surrounded by classical sculpture – a dream world for any eager artist of the time. Works depicted in Federico’s drawing include Laocoön and His Two Sons, Apollo Belevedere, and Tiber and Nile, the river god sculptures. Unfortunately, such a vast array and contrappasto of works are no longer located all together in the Courtyard. They are now in the Vatican Museums, where one can still stand in awe of the classical masters, just as the Zuccaro brothers once did.

(Brooks, Julian. Taddeo and Federico Zuccaro: Artist-Brothers in Renaissance Rome. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. 2007 at bettybaroque.wordpress.com)

Timeline:

1585-Painted Doge’s Palace in Venice

1594-Worked on the adoration of the Magi (cathedral, Lucca) demonstrates greater oncessions to naturalism foreshadowing the baroque 16th century

-Helped develop the Mannerist style in Central Italy during the mid-16th century

-Among Federico’s important works is the large Barbarossa making obeisance to the Pope

-Federico established the Academy of Saint Luke in his own house in Rome (now Biblioteca Hertiziana)

1607-He was also in a theoretician; his L’Idea de’scultori, pittori et architetti (The idea of sculpture, painting and architecture), was first published in Turin

1609-Died on July 20

(s9.com)

.+Rebecca+Orne+(later+Mrs.+Joseph+Cabot).+Worcester+Museum+of++Art..jpg)

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar